On the 2nd February 2024 from Nairobi airport, where I stopped for eight days of meetings with my brothers, I landed in Goma, the main city of Kivu, the large region in eastern Congo.

I say to myself that I am truly in Africa now. I am immediately overwhelmed by the many people crowding the streets, including people on foot and countless motorbikes racing around in all possible ways, livening up the streets despite themselves. On the edges there are a thousand small markets, where you can find everything. Many colours and smells, people arguing, surely to negotiate a price, others who knows why. People are still in relationship with each other, according to a secret plan that makes the streets so lively.

Walking along them I immediately see a long decrepit wall surmounted by a safety net. It has many cracks and many colors. It immediately strikes me as an image of this tormented country. A basic colour, a great resource of humanity and nature, burned into many others; so many cracks that seem to make him fall, yet he resists; a network that wants to defend, but cannot.

As I meet people, I listen to the stories of a war that has dragged on for almost thirty years. This borderland is too rich in mineral resources and this appeals to the unscrupulous appetites of too many in the world. We all know that our cell phones wouldn’t work without coltan, which is abundant here. Some told me that their relatives and farmer acquaintances have found gold and other minerals just by moving the soil.

The area is also a border area and, as always, everyone claims that land. International powers, from countries to many financial entities, want to obtain political advantages and enormous profits. All this passes through the people I see passing as if in a film before my eyes, actors unaware of a drama that far surpasses them.

I meet adults and young people, even kids and everyone tells me a little piece of this drama. I greet the bishop of Goma in his house, who, like an attentive shepherd, knows how to tell me what is happening. His enormous diocese is now divided in two due to clashes between rebels and the government and he himself cannot visit it in its entirety. He tells me about the recent meeting in Goma of the bishops of Congo, Rwanda and Burundi, a concrete sign of peace and possible reconciliation.

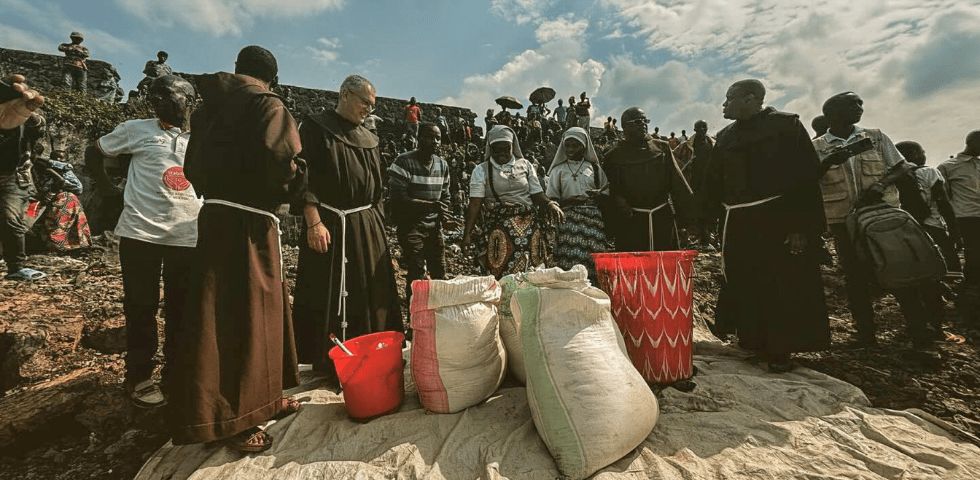

On the morning of the 3rd February, after prayer and a quick breakfast, the Franciscan friars and Religious Sisters who work there take me to a refugee camp. It is the smallest of the fourteen that surround the city with around 75 thousand people. The calculations are quickly done from 800 thousand to one million refugees from all over Kivu and also from neighboring countries, they are the guests of unspeakable misery.

We enter the field on tiptoe. Hundreds of people walking here too, it’s not clear why. It’s something that has surprised me since my first time on the continent. Everyone is walking, seemingly aimlessly. Of course, because few have the means, but there is something more. Moving, moving seems to be part of the deep soul of this country. The people here walk, and this describes their way of being in the world, as nomads.

Immediately children and women surround us. I greet, shake hands, caress many heads and faces. Openness on the one hand and modesty on the other reveal to me a way of being of these people and I am always fascinated by it. Suddenly a small woman comes towards us, shouting in Swahili and becoming agitated. For a moment she is almost scary, then we realize that she is like the village jester. She is a pygmy, and she says it with pride, claiming that this land belongs to her people who host all the others there. She begins to sing and dance, immediately involving everyone around us; in the darkness of this hell a light comes on thanks to madness, which makes us see reality in another way and releases the ability of these people wounded and violated in so many ways every day to find each other, unite, celebrate. The singing, the clapping hands and the dance steps transform reality and make you feel the desire for life and freedom that everyone carries within them, live embers under the ashes.

We arrive in front of a large depression in the ground, full of children and women, gathered in three groups and very agitated. It’s time to distribute a bowl of rice for the little ones. Among dust and waste, we descend into this great pit, where human beings, I repeat human beings, queue up and shout for a handful of rice. I’ve seen this scene many times before, but it’s still a punch in the stomach. In front of me, two children get into fights over nothing, violence is now part of their way of being. Many are well ordered in line and waiting. They are not surprised by our presence. They get close and then surround us. I find myself overwhelmed by little hands that want contact, that ask for things that are incomprehensible to me. With the Sisters I start distributing the already cooked rice. It’s a bowl game. They definitely notice that I am inexperienced and know that they can get more, and I put as much as I can into each container. I don’t think there will be a multiplication of rice, but I know it will be enough for everyone.

Children are the stigma of this war. In one of the tiny canvas tents that house these poor people, I enter and see four mothers with their few-day-old children. They welcome me with a beautiful smile and make room for me where there is no room. They hand me one of the babies, just three days old. The heart beats strong. Life is born in this bedlam and the mothers’ smiles reveal its full strength. It is women who bring this situation and keep it standing, despite everything.

I meet other children who are orphaned or abandoned at birth, perhaps the result of the countless violence that takes place in this land. One of them takes my glasses, wants to touch them, another wants to come in my arms, another pulls away. Their looks say everything, without words, like that of the elderly women, beautiful and full of dignity with their wrinkles, canes, and uncertain steps.

These people lived in their villages in a dignified and safe manner. They were driven out by war, by the violent raids of various armies, by large foreign companies that burnt land to deforest and exploit excessively rich land without scruples. They are justnumbers.

The children don’t want to let us go. While we are surrounded by them, we talk to those in charge of the camp to understand what drop of life we can drop on this scorched earth.

They tell us that only last night a bomb fell near here, behind a school: the children were all safe. This miracle gives the measure of the strength of life. We can still hope. They tell us about the many, too many signs of trauma and mental suffering. Listening and help centers are needed.

Everything is needed. Above all, that many world powers, who do business here on the backs of these people and draw their spheres of influence and power there, sit down at a table and decide how to get out of this overly long stalemate.

A forgotten war, one of many. The poor pay the greatest consequences.

I leave the field shouting within myself: “Until when, O Lord?”.