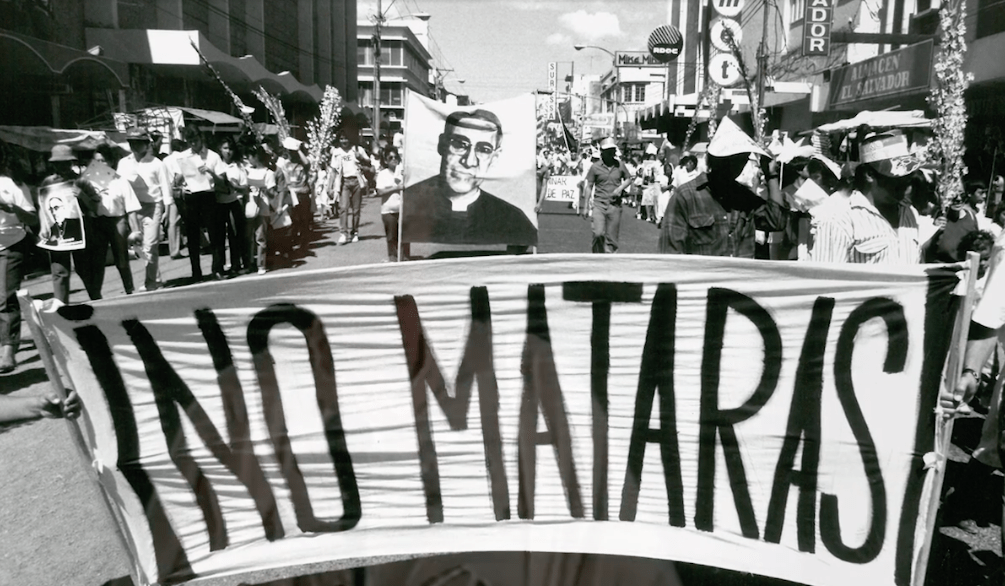

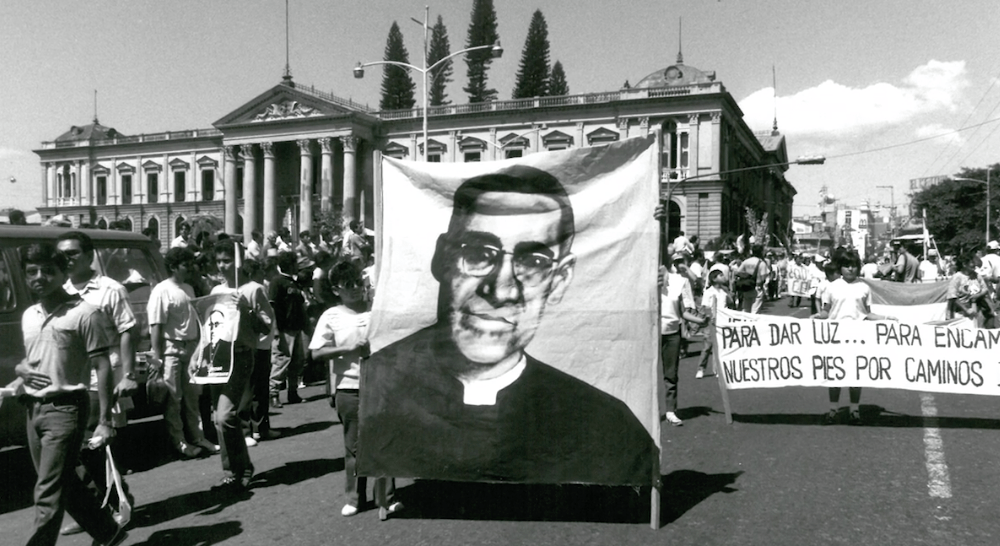

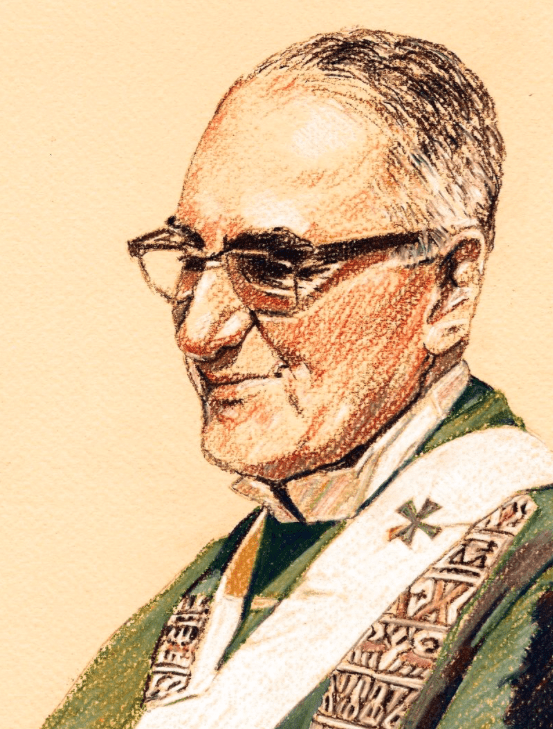

On March 24, 1980, St. Óscar Arnulfo Romero y Galdámez was martyred while celebrating the Eucharist.

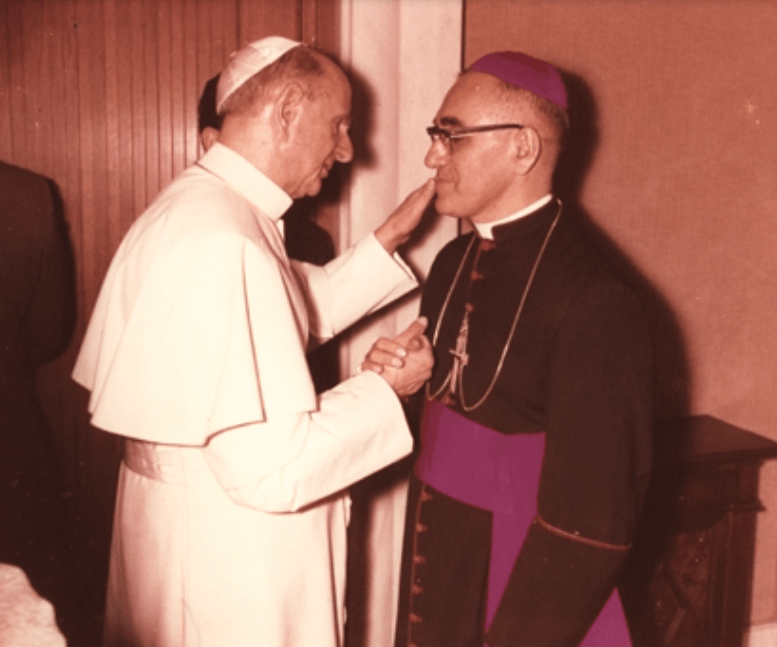

It is fitting that during March, the month of his death, we remember that day on October 14, 2018, when Pope Francis canonized him in St. Peter’s Square along with Pope Paul VI, Sr. Nazaria Ignacia March, Sr. María Caterina Kasper, Fr. Francesco Spinelli, Fr. Vincenzo Romano, and layman, Nunzio Sulprizi. That event caused many from around the world to rejoice, especially those who identify themselves with either Romero’s strong testimonials or with the way he followed the Lord. Here are a few reflections from Bishop Romero that can help us in our work as Friars Minor, especially in our work with JPIC.

We need to start with his understanding of the meaning of peace. Bishop Romero always begins from a premise of what peace is not, so he can move to address what peace actually is. We also need to put his homilies into context with a reality check from Salvadoran life at the time. It was March 12, 1977, and his personal friend, Father Rutilio Grande, S.J, was murdered. Additionally, the climate of persecution towards the Church was extreme, and Bishop Romero decided to no longer participate in any official act of the State until this murder was clarified and the climate of persecution of the Church stopped. His decision was communicated three days after the murder, March 15, 1977. Then, on July 1, 1977, four months after this event, a new president of El Salvador, General Carlos Humberto Romero (although they both have the same last name, they are not related) was sworn in. Keeping his word, Bishop Romero did not participate in any official government acts; at the same time, he clarified that “This is not to be interpreted as a declaration of war or a final break.”[1] In fact, in keeping with the spirit of Vatican II documents (GS 78) as well those as from the conference of the Latin American Bishops in “Medellín” in 1968 (M 2, 14), Romero reminds us of the following:

Both documents say that peace is not the absence of war. That is a totally negative notion. Nor can we say that we have peace just because there is no war. Currently, there is no war in many countries; in fact, most of the world is not at war, and yet, there is true peace in very few places. It is not enough to not have war. Nor is true peace the balance of two adversaries’ forces, claiming to be in harmony. Russia and the United States continue to be threats, even if there is civility between them. What remains though is fear, fear from all of the flexing as to who is more powerful. That it is not peace. If two boys or two men threaten a lawsuit against each other, but that lawsuit does not get to litigation, it cannot be considered peace either. There is still fear between two powers or the two parties. As the Pope has shared, nobody can talk about peace with a gun or a rifle in his hand; that is fear. There can be no peace either, says the Second Vatican Council, from the horrific quests for domination and wanting to subdue, whether it be a Nation or a single person. That would be like saying peace comes from death or repression. Neither of them is peace.[2]

What Bishop Romero was trying to say is that the presence of fear is actually a manifestation that peace cannot yet exist, and much less so when coupled with a power source that is categorically only looking for repression or death. Christian peace goes much further, much more profound.

So, what, then, is peace?

For Bishop Romero, peace is linked to justice and only from a justice perspective can it can be understood. That is why he reminds us: Peace, says the Second Vatican Council, has its definition from Isaiah,[3]the prophet, which Pius XII put as the motto on his crest: Opus justitiae pax. Peace is the fruit of justice. That is peace. Peace will only exist when there is justice. And yet, we liked listening to this concept in the presidential addresses.[4] When there is justice, there is peace. But without justice, there is no peace. God expects us to bring about peace, yet while we are working to bring it about, we need to see peace as a fantastic tangible reality waiting out there in the middle of society for us to seize. This prize, peace, may come when there is no further repression, when segregation has disappeared, when all people can enjoy their legitimate rights, when there is freedom, when there is no fear, when Nations are not suffocated by their weapons, when there are no dungeons that cry out because God’s children have lost their freedom, when human torture becomes a past, and when human rights are no longer trampled upon.[5]

For our Saint, peace is based on justice; but to get to that kind of justice, collaboration is necessary, coupled with the dedicated and hard work by people of good will. This implies a genuine effort on the part of humankind to commit and work for peace from that base of justice. The level of real respect for human rights is the gauge to know if there can be peace. It is equally important to want peace, to desire it and be conscious of the actual role that peace plays in society. The responsibility to work for peace can then be taken on, based on our awareness of peace’s role within our society. In that same sense, Romero shared the following:

If there is a genuine desire for peace, we know that justice will be the root of that peace. All who can abolish acts of violence are obliged to make those changes because Medellín[6]also reminds us that everyone who can do something for a fairer Latin America but does not do what is within his or her reach, sins against peace. We can only hope that the sins of omission that one confesses at the beginning of the Mass will touch the consciences of those who could do much, yet do not. Still, others may do little because they feel the need to remain in the good graces of the powerful, to protect their income, or to avoid political problems. They would rather betray the Law of God and commit these sins of omission out for fear of losing their way of life. Rather than being a breath of peace so true justice can prevail, these same people do not do what they should be doing for their fellow citizens, for their Nations, for the larger society, or the common good.[7]

In other words, to achieve peace, a personal commitment to work towards it is necessary, one that comes to know that our individual actions, both from our homes and workplaces, are necessary to influence peace.

And yet, for us as Friars Minor, from a perspective of Justice, Peace and Integrity of Creation (JPIC), we not only have the opportunity to work for that peace, but we too are guilty of omission when we do not put forth concrete actions to promote peace. JPIC is one specific setting that allows us to carry out explicit actions in favor of peace for our brothers and sisters.

Fight for peace, but without violence

The work and commitment for peace do not mean committing acts of violence; violence cannot be justified if we seek peace. That is why our martyr reminds us of the following:

We can never justify violence. “Violence” from both Vatican Council II and Medellín,[8]along with the Pope, “is neither Christian nor Gospel. Christians are peaceful and are not ashamed of it.” The Christian knows that he can fight, but his Gospel invites him to the defense of justice. He is courageous, but he knows that violence only breeds violence, and like war, must be the last resort when all peaceful resources have been eliminated. Where violence exists, it depletes the capacity for peace, a peace that could be fertile and productive, because violence gives in to the passions of hatred and resentment rather than creating resolutions to bring about peace. To get to peace, it is imperative that the children of peace, the children of God who work to better this world (even for non-Christian peace movements) are to be inspired not by violence, but by peace that bears fruit, demands the realization of rights and demands respect for human dignity, and peace which never accepts to close eyes so as to avoid problems with those who trample the rights of humanity. Governments can also be great crafters of peace, as long as they do not interfere with the Church’s freedom to preach her Gospel, along with the same freedom to preach the dignity of the human person. Truth be told, the government can find a no more effective and powerful collaborator in our world than with the Church, proclaiming true liberty, justice and peace.[9]

In other words, if we become aware of our “being Church,” we become “effective” collaborators in our society in order to live in freedom, justice and peace.

Reaching the fortress of love

Working for peace from our Christian dimension implies being witnesses of what love means, a love that is actually experienced by men and women for having been loved by God. That is why Saint Romero reminds us:

Justice is not enough; love is necessary. We have always preached this, brothers and sisters. I take some pleasure to point out that all those who have followed the thinking of the Church during these times have never heard a word of violence from my lips. The strength of a Christian is love, as we have said. And we repeat: the strength of the Church is love. A love that makes us feel like brothers and sisters to all, the brother or sister that Saint Paul[10]proclaims in today’s second reading, who is inspired by the one who loved us unto death and is why we are drawn to the love of Christ crucified: so we can be love for our brothers and sisters. Until we can reach such strength of love, we can never be true peacemakers. You cannot be the architect of peace with a heart that is resentful, violent, or filled with hate. You have to know how to love, like Christ did, even loving those who crucified Him: Forgive them, Father, they do not know what they are doing. They are worshipers of money and power. If they knew you, they would love you. That is why, rather than hate and resentment, I actually pity those poor ones who do not know the strength of the love that You have given me. Lord, give them love, too. How much good could the powerful do, if they truly loved and were not selfish and envious? How beautiful the world would be, brothers and sisters if we all develop such a force of love.[11]

Thanks to this experience of letting yourself be loved by the Lord, you can work effectively to pursue peace. The experience of being forgiven and loved allows us to approach and understand others from an experience of love. Only by that experience of love, can we reach a true peace where there is no longer any room for resentment, jealousy, or violence. He who lives the experience of being loved by God knows and understands how to forgive. Let us ask San Francis to intercede for us before the Lord so that today we can be “instruments of your peace,” motivated by St. Óscar Romero.

Br. Carlos Omar Durán Vásquez, OFM

Province of Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe– Central America

[1]Romero, O.A. Homilías, I, UCA editores, El Salvador, 2015, 167

[2]Romero, O.A., Homilías, I, 170

[3]Isaiah 32, 17

[4]Cf. Romero, Homilías, I, 169. President Romero shared in his inaugural speech his great desire to search for peace. Bishop Romero, as his counterpart shared his concern if the path for peace goes down false roads to look for it. What the Church brings to the table is true dialog with the economic and political powers, but with the voice of the Gospel.

[5]Ibid., 170-171

[6]M 2, #18

[7]Romero, Homilías, I, 171-172

[8]M 2, #15

[9] Romero, Homilías, I, 171-172

[10] Galatians 6: 14-18

[11] Romero, Homilías, I, 172-173